The antidote to many of our mental health crises must come from rebuilding society and forming a culture of community rather than a culture of hostility and toxicity.

Van Gogh – Starry Night. (Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

By Vijay Prashad

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

men 1930, Clément Fraisse (1901–1980), a shepherd from the Lozère region of France, was confined to a nearby mental hospital after he tried to burn down his parents’ farm.

men 1930, Clément Fraisse (1901–1980), a shepherd from the Lozère region of France, was confined to a nearby mental hospital after he tried to burn down his parents’ farm.

For two years he was kept in a dark, cramped cell. Using a spoon, and later the handle of his pot, Fraisse carved symmetrical figures into the rough wooden walls that enclosed it. Despite the inhumane conditions in these mental hospitals, Fraisse made beautiful art in the darkness of his cell.

Not far from Lozère is the Abbey of Saint Paul de Mausole in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where Vincent van Gogh had been confined four decades earlier (1889–1890) and where he completed around 150 paintings, including several important works , including them The starry night in 1889.

I was thinking of both Fraisse and Van Gogh when I visited the old Ospedale Psichiatrico Giudiziario (OPG) in Naples, Italy, in September for a festival held at this former criminal asylum, which once housed those who had committed serious crimes and were deemed insane .

Located in the heart of Naples at Monte di Sant’Eframo, the grand building was first a monastery (1573–1859), then a military barracks for the Savoy regime at the unification of Italy in 1861, and then a prison set up by the Fascist regime in the 1920s. .

The prison was closed in 2008 and then, in 2015, occupied by a group of people who would later found the political organization Potere al Popolo! (Power to the people!). They renamed the building Ex OPG – Je so’ pazzo; “former” meaning the building is no longer an asylum and “Je so’ pazzo” referring to the favorite song of the beloved local singer Pino Daniele (1955–2015), who died around the time the building was occupied:

I’m crazy. I’m crazy.

The people are waiting for me.

….

I want to live at least one day as a lion.

I’m crazy, I’m crazy.

I have the people waiting for me.

….

In life I want to live at least one day as a lion.

Today the Ex OPG is home to legal and medical offices, a gym, theater and bar. It is a place of reflection, a hub of people designed to build community and confront the loneliness and uncertainty of capitalism. It’s a rare kind of organization in our world, where fed-up communities are increasingly isolated and individuals, trapped in a prison of frustrated expectations, nevertheless hope to use their meager tools (a spoon, a crock pot handle) to shape their dreams and reach the starry sky.

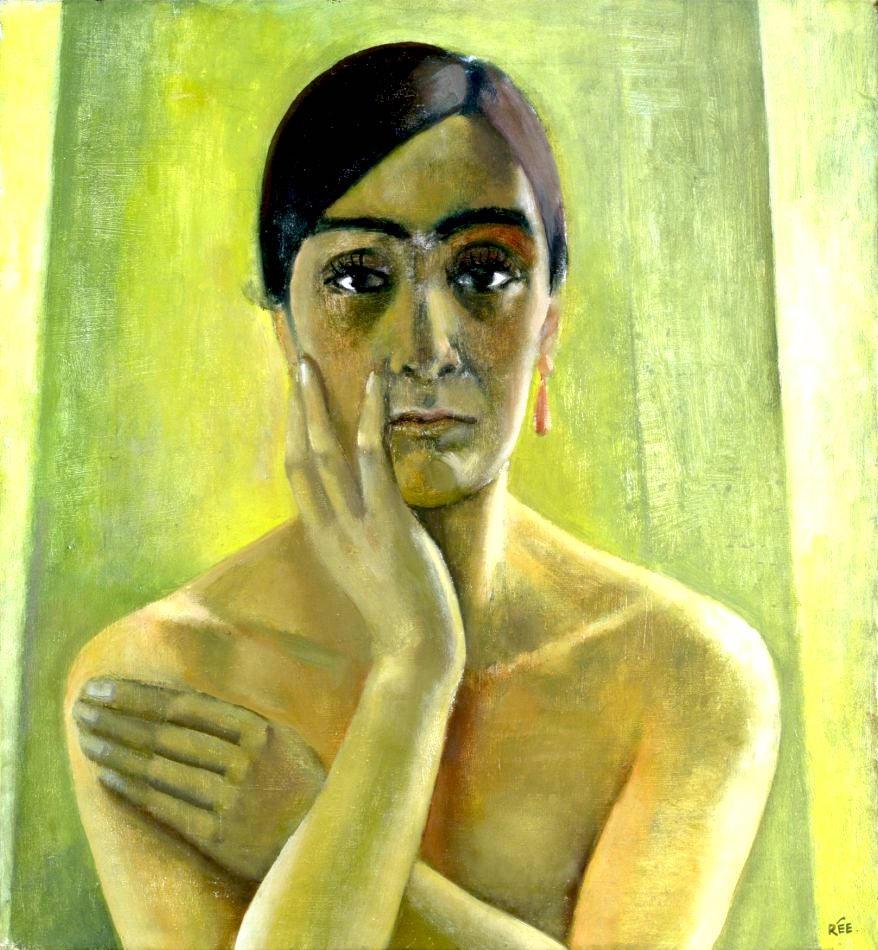

Anita Rée, Germany, “Self-Portrait,” 1930. Rée (1885–1933) killed herself after the Nazis declared her work “degenerate.” (Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Even the World Health Organization (WHO) does not have sufficient data on mental health, mainly because poorer nations cannot keep accurate records of the enormous psychological struggles of their populations. Therefore, the focus is often limited to the wealthier countries, where such data is collected by the government and where there is greater access to mental health care and medication.

A recent survey of 31 countries (mostly in Europe and North America, but also including some poorer nations such as Brazil, India and South Africa) shows changing attitudes and increasing concern about mental health.

The survey found that 45 percent of respondents chose mental health as the “biggest health issue people face [their] country today,” which is a significant increase from the previous survey, conducted in 2018, where the figure was 27 percent. Third on the list of health challenges is stress, with 31 percent choosing it as a top concern.

Please Give Today to CN

Autumn fund Drive

There is a significant gender gap in attitudes towards mental health among young people, with 55 per cent of young women choosing it as one of their main health concerns, compared to 37 per cent of young men (reflecting the fact that women are disproportionately affected by mental health issues).

While it is true that the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated mental health issues around the world, this was a crisis before the coronavirus. Data from the Global Health Data Exchange shows that in 2019 – before the pandemic – 1 in 8, or 970 million, had a mental disorder worldwide, with 301 million struggling with anxiety and 280 million with depression. These numbers should be seen as an estimate, a minimal picture of a serious crisis of unhappiness and maladjustment to the current social order.

There are a number of conditions that go by the name of “mental disorder”, from schizophrenia to depression that can lead to suicidal thoughts. According to a 2022 WHO report, 1 in 200 adults will suffer from schizophrenia, which on average leads to a 10 to 20 year reduction in life expectancy.

Meanwhile, suicide, the leading cause of death among young people globally, is responsible for 1 in 100 deaths (note that only 1 in 20 attempts result in death). We can create new charts, revise our calculations, and write longer reports, but none of this can alleviate the profound social neglect that pervades our world.

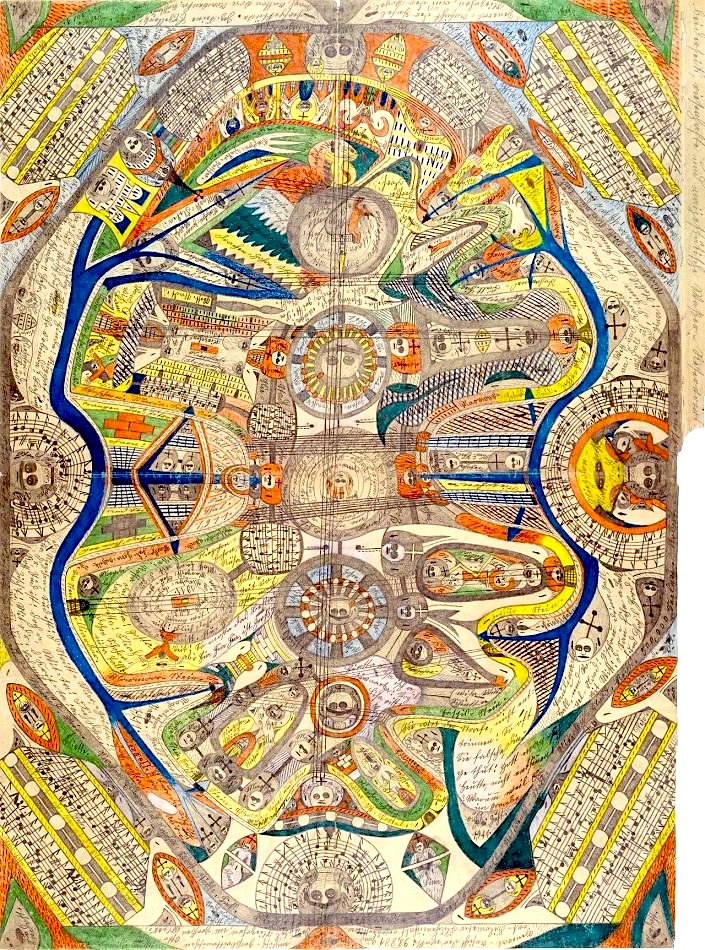

Adolf Wölfli, Switzerland, “General View of the Island Neveranger,” 1911. Wölfli (1864–1930) was abused as a child, sold as a laborer, and then employed at the Waldau Clinic in Bern, where he painted for the rest of his life. his life. (Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Negligence isn’t even the right word. The prevailing attitude towards mental disorders is to treat them as biological problems that require only individualized drug treatment. Even if we were to accept this limited conceptual framework, it still requires governments to support the training of psychiatrists, make drugs affordable and accessible to the population, and integrate mental health treatment into the wider health system.

However, in 2022, the WHO found that on average, countries spend only 2 percent of their health budgets on mental health. The organization also found that half of the world’s population – mostly in poorer nations – lives in situations where there is one psychiatrist to serve 200,000 or more people. This is a state of affairs where we are witnessing a general decline in health budgets and public education about the need for a generous approach to mental health issues.

The latest WHO data (December 2023), which covers the rise in pandemic-related health spending, shows that in 2021 health spending in most countries was less than five percent of GDP.

At the same time, in its 2024 report A world of debt, The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) shows that almost a hundred countries spent more on paying off their debts than on healthcare. While these are forbidding statistics, they do not get to the heart of the problem.

Over the past century, responses to mental health disorders have been overwhelmingly individualized, with treatments ranging from different therapies to prescribing different medications.

Part of the failure to address the many mental health crises—from depression to schizophrenia—has been a refusal to accept that these problems are not only influenced by biological factors but can be—and often are—created and exacerbated by societal structures.

Dr. Joanna Moncrieff, one of the founders of the Critical Psychiatry Network, writes that “none of the conditions we call mental disorders has been convincingly shown to result from biological disease,” or more precisely, “from a specific disruption of physiological or biochemical processes.” This is not to say that biology does not play a role, but simply that it is not the only factor that should shape our understanding of such disorders.

In his widely read classic The health association (1955), Erich Fromm (1900–1980) drew on the insights of Karl Marx to develop an accurate reading of the psychological landscape of a capitalist system. His insights are worth revisiting (forgive Fromm’s masculine use of the word “man” and the pronoun “his” to refer to all of humanity):

“Whether the individual is healthy or not is primarily not individual, but depends on the structure of his society. A healthy society increases man’s capacity to love his fellow man, to work creatively, to develop his reason and objectivity, to have a self-awareness based on the experience of his productive capacity. An unhealthy society is a society that creates mutual enmity, mistrust, that turns man into a tool for use and exploitation by others, that deprives him of self-awareness, except to the extent that he submits to others or becomes automatic. The community can have both roles; it can enhance the healthy development of man and it can hinder it; in fact, most societies do both, and the question is just to what extent and in which directions their positive and negative effects are applied.”

The antidote to many of our mental health crises must come from rebuilding society and forming a culture of community rather than a culture of hostility and toxicity. Imagine if we build cities with more community centers, more places like “Ex OPG – Je so’ pazzo” in Naples, more places for young people to gather and build social relationships and their personality and confidence. Imagine if we spent more of our resources teaching people to play music and organize sports games, read and write poetry, and organize socially productive activities in our neighborhoods.

These community centers could house health clinics, youth programs, social workers and therapists. Imagine the celebrations such centers could produce, the music and joy, the power of events like Red Book Day. Imagine the activities—mural painting, neighborhood cleanups, and garden plantings—that could occur when these centers fuel conversations about the kind of world people want to build. Indeed, we do not have to imagine any of this: it is already with us in small gestures, whether in Naples or in Delhi, in Johannesburg or in Santiago.

“I think depression is boring,” wrote the poet Anne Sexton (1928–1974). “I’d do better to make soup and light the cave.” So let’s make soup at a community center, pick up guitars and drumsticks, and dance and dance and dance until this great feeling comes over everyone to join in healing our broken humanity.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writer and chief correspondent for the Globetrotter. He is editor of LeftWord Books and director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior foreign fellow at the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The darker nations and Poorer nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and with Noam Chomsky, The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of American Power.

This article is from People’s Dispatch and was produced by Globetrotter.

The views expressed in this article may not reflect the views Consortium News.

Please Give Today to CN Autumn fund Drive

Viewing posts: 3,293

#Vijay #Prashad #suffer #sanity